|

|

|

|

|

|

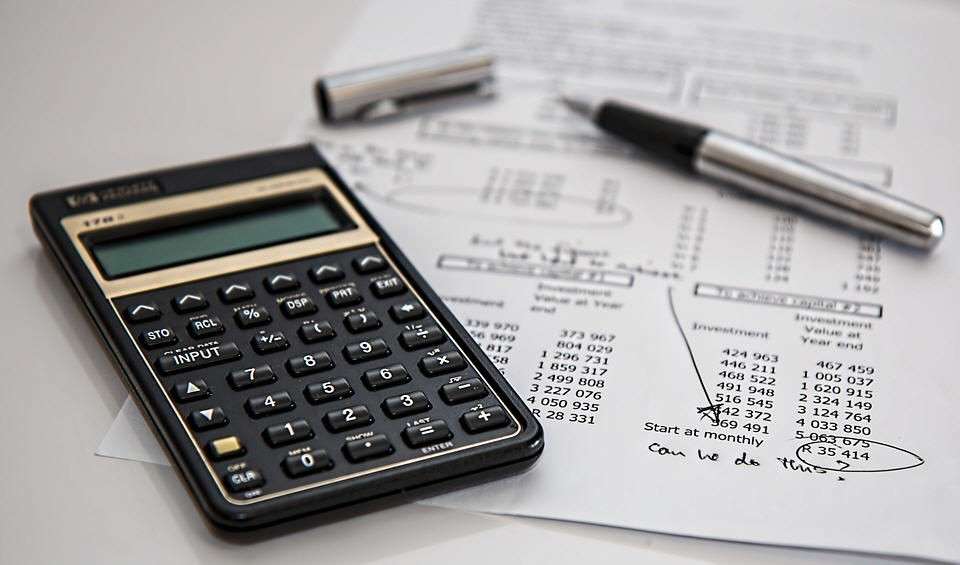

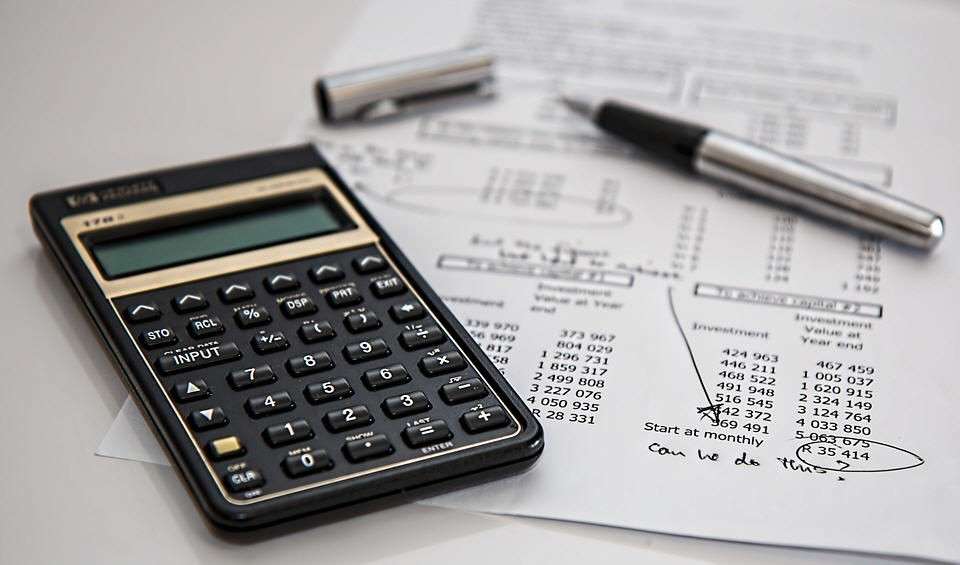

In 2015, the government introduced the

"bright-line test", a method which attempts to tighten the property investment

rules.

The bright-line test states that

(subject to exemptions) any gain from disposing of residential land within two

years of acquiring it will be taxable. The test only applies to residential

land. Residential land is land that has a dwelling on it or could have a

dwelling on it and does not include farms or business premises.

The

bright-line test applies where a person's "first interest" in residential land

is acquired on or after 1 October 2015. Generally, a person acquires their

"first interest" on the day they enter into an agreement to purchase

residential land. The start and end dates may vary depending on the

circumstances of each transaction. The

bright-line test applies where a person's "first interest" in residential land

is acquired on or after 1 October 2015. Generally, a person acquires their

"first interest" on the day they enter into an agreement to purchase

residential land. The start and end dates may vary depending on the

circumstances of each transaction.

For standard sales, the two year

bright-line period starts when title for the residential land is transferred

to a person under the Land Transfer Act 1952 and ends when the person signs a

contract to sell the land. In other situations, such as gifts, the date of

"first interest" is the date the title is registered by the donor and the end

date is when the donee acquires registered title.

In simple terms, when a person purchases

their main home after 1 October 2015 and then sells it within two years, the

income they receive for the sale is not taxable. A person can only have one

main home to which the bright-line test does not apply. If a person has more

than one home, it is the home that the person has the greatest connection with

that is considered the main home for the purposes of the test. Factors to

assess when determining what constitutes a main home include; how often a

person uses the home, where their immediate family is, where their social and

economic ties are and whether their personal property is in the home.

The test is based on actual use of the

property and not just a person’s intention to use the property as a main home.

This exemption cannot be applied on a proportionate basis; therefore, if a

house is used only partly as a main home, the exemption does not apply. Where

a main home is held in a trust, the exemption is usually available; however,

additional information is required to ensure trusts are not used to avoid tax.

|

|

Inside this edition

The

Bright-line Test

The Human Tissues Act

I have been named an executor of a will,

what do I do now?

Reckless

Trading

Small Passenger

Services Review

Snippets

Queen's Chain

The Ombudsmen

Print version

A habitual seller cannot use the main

home exemption. If a person has used the main home exemption more than twice

in the previous two years at the time of selling their property, they are

considered a habitual seller. A habitual seller also includes a person who

regularly acquires and disposes residential land. Where property is inherited

by a person as a beneficiary and they subsequently sell the property, the

disposal will not be subject to tax under the bright-line test. Where property

is transferred between partners or spouses under a property relationship

agreement, there are no tax implications. However, if the property is

subsequently sold; the bright-line test may apply.

There have been cases where tax

obligations arose through the disposal of residential property which did not

result in financial gain to the seller. As a result, it is highly recommended

that specialist advice is obtained in respect of all property transactions.

Top

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Until we are

confronted with death, an emergency or illness, few of us are likely to turn

our minds to the interplay between the law, and how it affects the way we deal

with a loved one’s remains, let alone the choices we make or leave in respect

of our own bodies.

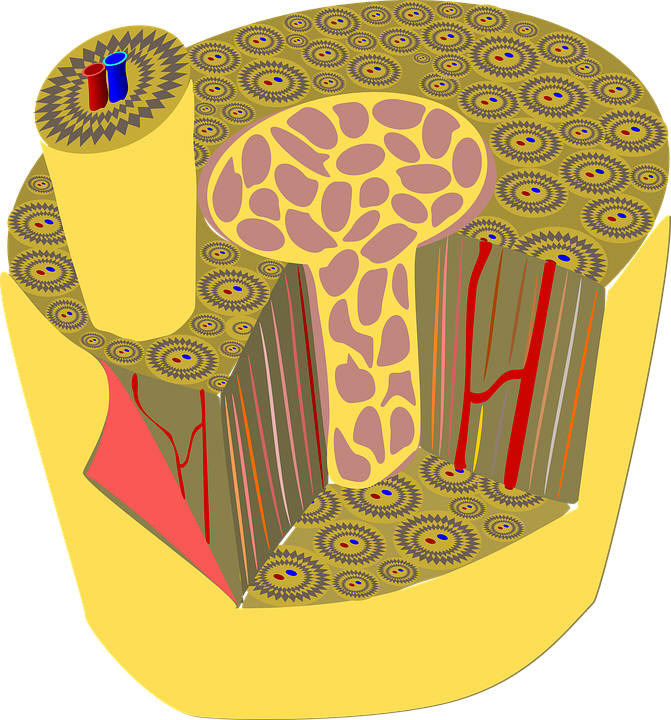

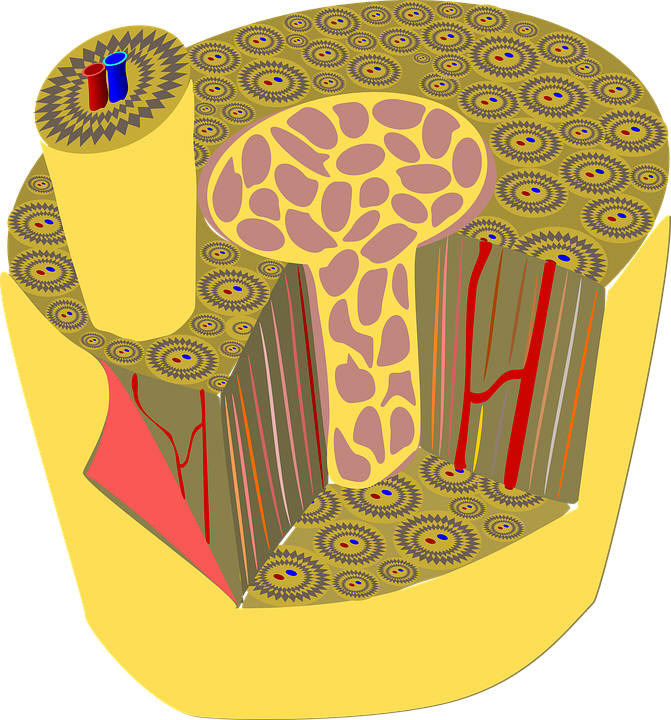

The Human

Tissue Act 2008 ("the Act") currently governs the way human tissue is dealt

within New Zealand. Under the Act, Human Tissue ("tissue") is defined as

including any material that is, or is derived from a body or material

collected from a living individual. The definition is wide reaching and

encompasses amongst other matters an individual’s organs, blood, skin or stem

cells. Human embryo's, including female eggs and sperm only qualify as human

tissue in certain instances, including where human tissue is collected for

non-therapeutic purposes or in relation to exporting or importing human

tissue.

The Act

provides for compromise in its framework, by facilitating an 'opt in'

approach. Informed consent or an informed objection may be given by the

individual whose body the tissue may be collected during their life and upon

death. Where no informed consent has been given or no informed objection has

been raised, the Act provides a hierarchy of who may consent to tissue being

collected from the body of a deceased, including an individual’s nominee(s),

immediate family and then a close available relative.

Several

assumptions exist within the Act, including:

a) that an individual over 16 years of age is capable of making an informed

decision;

b) consent or objection is free and informed, immediate family members

providing consent have undertaken consultation with other immediate family

members; and

c) that the individuals have taken into account the cultural beliefs of their

families.

The cultural

context for decision making in respect of donating or collecting tissue is

woven throughout the Act. There is a requirement and expectation on those who

collect human tissue, that they will take into account the spiritual needs,

values and beliefs of the individual and their immediate family. Potential

donators are encouraged to consider the impact that their decision will have

on their family following death.

|

|

In respect of

expressing consent, certain obstacles exist in conveying ones wish to be a

donor. We are likely to be familiar with the 'donor' indications on a driver

licence. However, ticking the 'donor' box on a driver licence may not meet

accepted requirements for obtaining informed consent. This is primarily due to

the contention that a driver licence has a life span of 10 years, and it may

not reflect an individual's wishes at the time of death. In contrast, a Will

provides the unequivocal wishes and intentions of a deceased person including

an expression of consent.

The issue of

expressing consent by way of a person's Will is that it may not be practical

and timely to ascertain certainty around the intention and consent of the

deceased in times of emergency, or where a timely decision is required. The

Act has attempted to alleviate this problem by providing an 'opt-in register',

where consent may be given after the fact and at a later date.

Top

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

When a loved one passes away it can be a

stressful time for the family, which can be made more difficult when the

deceased has not left a Will. Where the deceased has left a Will they will

have named their executor or executors (their representative(s) in that Will.

The role of an executor is to administer

the deceased's estate. This may include settling outstanding debts owed by the

deceased, and distributing the deceased's estate in accordance with the

deceased's Will.

Before an executor can administer the estate of the deceased, they must first

obtain Probate.

What is "probate"?

Probate is a court order determining the Will of the deceased as being true

and authentic. The executor(s) is/are appointed in this order. Upon the making

of the order, the executor(s) then has/have the legal authority to deal with

the deceased’s estate.

How do I apply for probate?

The executor(s) named in a Will must make an application in writing to the

Wellington High Court for probate. The application must be in a specific

format, as prescribed by a set of rules called the High Court Rules.

An application for probate may be filed in one of two ways either by way of

"probate in common form" or by way of "probate in solemn form".

An application for "probate in common form" is usually made on a "without

notice" basis, where the application is made without notifying anyone else, on

the basis that no one will contest the Will.

In the event that it is highly likely that someone will contest the Will, an

application for 'probate in solemn form' will need to be filed. In these

circumstances the relevant parties will be notified of the application and a

trial at High Court will proceed, for which the parties will probably need

legal advice.

|

|

What would I need to make an

application for Probate?

The High Court application fee for obtaining Probate is currently $200.00;

this would need to be paid together with the filing of the following

documents:

* The original Will (not a copy);

* An application for probate in common or solemn form;

* A sworn statement (affidavit) from the executor(s) which includes the

following information;

* The person who made the Will has died;

* They knew the deceased;

* Where the deceased was living when they died; and

* Confirmation that the Will is the deceased's last Will.

How long does this process take?

If the Application has been drafted correctly, in the prescribed from, and

filed acceptably with the Wellington High Court, it may take four to six weeks

to process the application. However, it could take longer if the High Court is

busy or the application is complicated.

This timeframe may also be drawn-out in the event that the application has not

been drafted correctly and/or the High Court raises issues with the

application. Delays of this nature have the potential to cause a number of

problems between the beneficiaries, and can affect an executor's ability to

administer the deceased's estate, particularly if immediate action is required

(which it often is).

With that in mind, legal advice should obtained when making an application for

Probate.

Top

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

The Companies Act 1993 ('the Act')

provides the framework that applies in respect of directors' duties and

reckless trading. The Act prohibits a director from allowing the business to

be carried on in a manner likely to create a substantial risk of serious loss

to the company's creditors. Any director who fails to exercise necessary care

or prudence may be found personally liable for reckless trading.

New Zealand’s largest award against a director for reckless trading was made

out in the Lower v Traveller [2005] NZSC 79 case. The High Court in this

particular case (and subsequently the Court of Appeal) determined that the

director was responsible for $8.4 million in damages.

Reckless trading refers to a director taking illegitimate business risks. In

determining the legitimacy of such risks, an objective assessment is

undertaken, with focus on the way the business is done, and whether the

director's methods have created a substantial risk of serious loss.

The courts have stipulated that a director's "sober" assessment of the ongoing

character of the company and its likely future income prospects is required

when a company hits troubled waters.

A two pronged approach to determine a director's liability has been adopted,

firstly whether there should be liability, and if required, what relief is

appropriate.

Material factors to assess that a

business risk is legitimate include whether:

(a) The risk was fully understood by those whose funds were at risk;

(b) The company was insolvent and continued to trade over an extended period;

(c) The director's conduct was normal, in its ordinary course of business; and

(d) The primary persons interested in the insolvent company are the creditors

rather than the shareholders.

|

|

Liability for reckless trading

can relate to an isolated transaction. The company does not need to be in

liquidation and no knowledge of the reckless trading is required.

There are limitations to the Act. The courts have found that recklessness

requires more than mere negligence; and a director must either be willfully

negligent or make a conscious decision to allow the business to be conducted

in a manner that causes substantial risk of serious loss to the company's

creditors. A director may also avoid liability where a director has the full

support of the creditors and the creditors were fully aware of risks which

were incidentally substantial.

One of the criticisms of reckless trading is that it does not allow for high

risk company trade where there are prospects of large profit margins. Some do

not consider this point well founded, as arguably a risk of loss is reasonably

balanced by a prospect of gain. It appears this point is yet to be decisively

settled at common law. The wording of the Act does not leave room for a

balancing exercise, however the Courts have acknowledged certain academic

articles which analyse the duties of directors under the Companies Act 1993,

proposing their preparedness to apply such an assessment to balance risk and

reward.

Top |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

The In April 2016, Uber (the private

passenger service operating via a social media smartphone application) came

under fire from the New Zealand Government, amidst fears that Uber was

changing its rules by dropping its requirements to have a passenger

endorsement for their licensed drivers or a certificate of fitness for their

cars. Uber was able to do so via some gaps in the relevant law. It was clear

that the law was unable to manage this new and fast growing development.

It transpired that Uber drivers were not legally required to carry any

licenses or endorsements which were imposed on ordinary taxi drivers. As a

result Uber drivers had lower overheads and were not obliged to follow any

formal regulations, despite the fact that they provided services almost

identical to those offered by taxi drivers. This fact was clearly a concern

for taxi drivers.

Further, and more concerning for the general public, Uber was legally

permitted to engage drivers who were convicted of serious crimes, or who were

medically unfit to drive to carry passengers. The law was in need of

modernisation and on 12 September 2016, Transport Minister Simon Bridges

introduced the Land Transport Amendment Bill to Parliament in an effort to

update the law applying to small passenger services, update the rules for

heavy vehicles and generals improve road safety.

|

|

The Bill, together with amendments to land transport rules

and regulations, aims to provide direction and much needed guidance to

encompass new technologies including smartphone apps. The effect of

modernising these regulations by way of the Bill would ensure that they are

flexible enough to accommodate new business models, while managing safety

risks.

The proposed changes aim to ensure an effective small passenger service sector

making services offered by that sector safe and accessible; improving the

effectiveness of the transport system and helping to reduce congestion.

The overarching purpose of the changes is to encourage innovation in transport

while managing safety risks to drivers and passengers.

To achieve these lofty goals, the Bill makes it an absolute requirement for

all transport service drivers to be licensed. Currently drivers seeking to

obtain a 'P' endorsement license (Passenger Endorsement License) must hold a

passenger endorsement certificate allowing the driver to be "hired" and the

change will mean that Uber drivers must do the same.

In addition, Uber drivers will need to, as part of obtaining the passenger

endorsement certificate, undergo a "fit and proper person check", which is

repeated every year by NZTA. The check examines things such as traffic

offending, previous complaints, serious behavioural issues, and always

includes a police check for criminal offending, including overseas

convictions.

The Bill has made it through its first reading in Parliament (15 September

2016) and appears to be on track to become law relatively soon. In any event

it is likely that the New Zealand Government will look to implement updated

legislation and regulatory requirements in other industries in order to meet

the demands of existing and future disruptive emerging services. It would

appear that Uber has become a much needed catalyst for legislative

modernisation.

Top

|

|

|

|

Snippets

|

|

|

|

Queen's Chain

Historically, the term 'chain' has

been used to express a unit of measurement in respect of land and distance.

Coincidently, the "Queen's Chain" describes the kilometres of Crown land which

exists throughout New Zealand to provide the public with access to coastlines,

rivers, lakes and native bush.

In reality, the Queen's Chain is a term describing what is now generally

accepted as the marginal strips of land or esplanade strips, which are

normally 20 metres wide and adjoining many lakes, rivers and the foreshore. It

can also include land which has been retained by the Crown for conservation

purposes. These lands are usually controlled by the Department of

Conservation. In some instances, this means there are restrictions on public

access. These restrictions are most commonly imposed to protect sensitive

areas or endangered animals.

However, there is still a large amount of privately owned land around New

Zealand which is not owned by the Crown. The private rights attached to such

land are referred to as "riparian rights" and usually extend well into the

water, granting unrestricted access to the owner. In any event, whether the

land is considered to be part of the "Queen’s Chain" or privately owned,

government imposed legislation still applies.

The Queen's Chain becomes a topic of contention when it comes to public access

to waterways and bush and there is often an assumption that the Queen's Chain

applies; when in many cases the adjacent landowner actually holds riparian

rights. Archives New Zealand holds records for all Crown land (including land

subject to the Queen’s Chain) which can be ordered and/or viewed in person.

Information on accessing such records may be at this address:

http://archives.govt.nz/research

Top

|

|

The Ombudsmen

The Office of the Ombudsman is an independent authority

which handles complaints and investigates New Zealand's government agencies.

Investigations are initiated following receipt of a complaint or on the

Offices' own initiative to address wider administrative issues.

The Office manages complaints from individuals about the decisions and

administrative acts of government agencies including district health boards

and local government. This includes official information complaints which

arise where a request is made to a government agency. This may be to obtain

information and the applicant is not happy with the response, or the

information is not provided within 20 days.

On receipt of a written complaint, the Office may either resolve it without

further investigation or investigate further and form an opinion on whether or

not the agency has acted unreasonably. Agencies are not required to implement

the Offices' recommendations; however, usually they are accepted. The Office

also provides guidance and training to agencies before they implement policies

to mitigate future complaints against them by the public. Complaints relating

to private individuals or decisions by tribunals and courts are amongst some

areas that are outside the Offices' jurisdiction.

The Office may refuse to investigate a complaint if alternative remedies are

available, if the complaint is over a year old, if the complainant lacks

standing, or if the complaint is made in bad faith.

The Office provides a valuable and vital public service. More information on

the Office, its services and how to access them may be found at this address:

http://www.ombudsman.parliament.nz

Top

|

|

|

|

If you have any questions about the newsletter items,

please contact me, I am here to help.

Simon

Scannell

S J

Scannell & Co - 122

Queen Street East, Hastings

4122

Phone:

(06) 876 6699 or (021) 439567 Fax: (06) 876 4114 Email:

simon@scannelllaw.co.nz

All

information in this newsletter is to the best of the authors' knowledge true

and accurate. No

liability is assumed by the authors, or publishers, for any losses suffered

by any person relying directly or indirectly upon this newsletter. It

is recommended that clients should consult S J Scannell & Co before

acting upon this information.

Click here to subscribe to this newsletter

|

|

The

bright-line test applies where a person's "first interest" in residential land

is acquired on or after 1 October 2015. Generally, a person acquires their

"first interest" on the day they enter into an agreement to purchase

residential land. The start and end dates may vary depending on the

circumstances of each transaction.

The

bright-line test applies where a person's "first interest" in residential land

is acquired on or after 1 October 2015. Generally, a person acquires their

"first interest" on the day they enter into an agreement to purchase

residential land. The start and end dates may vary depending on the

circumstances of each transaction.